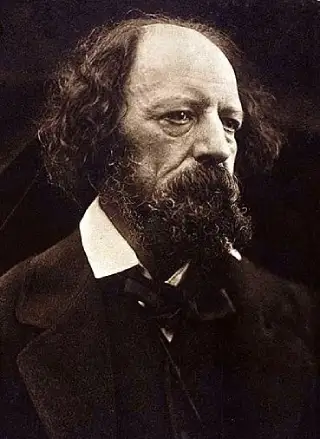

Biography of Alfred Lord Tennyson

| date | place | |

|---|---|---|

| born | August 06, 1809 | Somersby, England |

| died | October 06, 1892 | Lurgashall, England |

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892) was the leading English poet of the Victorian age and one of the most widely read writers in the English language. Born in Somersby, Lincolnshire, the son of a Church of England clergyman, he showed literary gifts early and entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1827. There he won the Chancellor’s Gold Medal with “Timbuctoo,” formed close friendships with members of the Apostles, and met Arthur Henry Hallam, whose early death in 1833 would shape Tennyson’s inner life and poetic vocation. Tennyson published “Poems, Chiefly Lyrical” (1830) and “Poems” (1832), withdrew for nearly a decade after hostile reviews, and returned decisively with the two-volume “Poems” of 1842, which established his reputation. In 1850 he married Emily Sellwood, published In Memoriam A.H.H., and was appointed Poet Laureate, succeeding Wordsworth. Settled at Farringford on the Isle of Wight (and later at Aldworth in Surrey), he produced a stream of popular and enduring works: “Ulysses,” “The Lady of Shalott,” “Locksley Hall,” “Tithonus,” “Morte d’Arthur,” the martial ode The Charge of the Light Brigade (1854), the psychologically daring “Maud” (1855), and the Arthurian cycle Idylls of the King (published between 1859 and 1885). In his later years he also wrote verse dramas—“Queen Mary,” “Harold,” and “Becket”—and in 1884 he accepted a peerage as Baron Tennyson of Aldworth and Freshwater, becoming the first major English poet to enter the House of Lords. He had two sons, Hallam (later Governor-General of Australia) and Lionel. Wealthy, famous, and much visited, Tennyson stood at the center of Victorian literary culture for more than forty years. As a poet, Tennyson refined an exquisite musicality of line, a sculptor’s precision of image, and a modern capacity for doubt tempered by faith. His verse marries sensuous surface to philosophical depth: the metrical grace of “The Lotos-Eaters” carries a meditation on weariness and duty; the lyrical refrains of “The Lady of Shalott” veil a parable of art, isolation, and desire; the dramatic monologues “Ulysses” and “Tithonus” probe restless will and the costs of immortality. Above all, In Memoriam is the Victorian elegy—an epic of grief and intellectual struggle that absorbs geology, evolutionary speculation, and Christian hope into a new kind of visionary hymn. Tennyson’s formal range is striking: he is a master of blank verse (the “Idylls”), of crafted stanzas with haunting refrains, and of the short lyric whose cadence lingers in the ear. His diction is impeccably chosen, rich in Anglo-Saxon roots that give weight and clarity, while his imagery—sea swells, autumn fields, starry distances, ringing metals—creates a world at once tactile and emblematic. He was, in temperament, both public bard and private seeker: a voice for empire, nation, and moral steadiness, and a solitary mind keenly alert to melancholy, doubt, and the fear that faith might fail. That duality—public assurance with interior questioning—makes him the representative poet of his century. Tennyson’s importance radiated beyond Britain and into American letters. His poems were staples of nineteenth-century U.S. schoolrooms and parlors; lines from “Break, Break, Break” and “The Charge of the Light Brigade” were among the most memorized in America. He offered American poets a model of technical finish and emotional resonance: Longfellow and Lowell admired his craft; editors and orators turned to his laureate voice for civic occasions; even poets who reacted against his polish—most notably Walt Whitman—defined themselves in relation to Tennyson’s measured music and public stature. His blank verse shaped American narrative and dramatic experiments, while the Idylls helped fix Arthurian romance at the center of English-language culture on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States, Tennyson became a touchstone of poetic authority—proof that a modern poet could speak to mass readership without surrendering complexity, and that elegance of form could carry contemporary anxieties about science, faith, and social change. Tennyson died on October 6, 1892, at Aldworth, his Surrey home, after a brief illness. The nation mourned; he was buried with honor in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner, near Chaucer and Wordsworth. Newspapers recounted the scene of his passing and the long twilight of his life, noting that the laureate of the Victorian age had gone “to where beyond these voices there is peace,” echoing his own “Crossing the Bar,” a poem he wished to stand at the end of his books. As a man and as a poet, Alfred, Lord Tennyson united reserve with warmth, meditation with music, and public responsibility with private courage. He gave the nineteenth century a language for grief and perseverance, for longing and resolve, and he gave later generations a standard of lyrical craftsmanship seldom surpassed. To read Tennyson is to hear the Victorian age thinking and feeling in verse; to return to him is to find, beneath the laureate laurel, a restless, humane intelligence that made beauty the vessel of truth.

Feel free to be first to leave comment.